- Home

- Dawn Dumont

Nobody Cries at Bingo

Nobody Cries at Bingo Read online

dawn dumont

© Dawn Dumont, 2011

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Thistledown Press Ltd.

118 - 20th Street West

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7M 0W6

www.thistledownpress.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Dumont, Dawn, 1978-

Nobody cries at bingo / Dawn Dumont.

ISBN 978-1-897235-84-3

I. Title.

PS8607.U445N63 2011 C813’.6 C2011-901709-1

Cover painting Neighbourhood Watch by Jim Logan

Cover and book design by Jackie Forrie

Printed and bound in Canada

Thistledown Press gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Saskatchewan Arts Board, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing program.

dawn dumont

For Nancy and Rose

CONTENTS

Young’s Point

I Slept There

A Spooky Halloween

Nobody Cries at Bingo

A Weighty Matter

The Beaver Dam

Boys Catch the Girls

Family Weddings

Miss Gramiak

Prep Work

The Indian Summer Games

Second Best Friend

The Conscience

The Way of the Sword

The Long Road to Freedom

We’ll Take the White One

The Reserve vs. Satan’s Brides

YOUNG’S POINT

I WAS BORN IN A SMALL SASKATCHEWAN TOWN called Balcarres. The town had given itself the nickname, the “Pride of the Prairies,” which is a pretty bold statement for a community that boasts more boarded up stores and businesses than regular ones.

Shortly after my debut, I was relocated to the Okanese reserve via a ride in our grandparents’ car. Okanese is Cree for Rosebud. The reserve doesn’t really have a nickname although many people have called it the “armpit of the universe,” usually after they lost an election.

We lived on the Okanese reserve in our green house on the hill with our mom and, sometimes, our dad, until our parents broke up for the 6,945th time. As they say, the 6,945th time is always the charm and Mom really committed herself to this breakup. She packed up our belongings in black garbage bags and moved me and my three siblings — my older sister Tabitha, my younger sister Celeste, and my younger brother David — six hours away from our home to The Pas, Manitoba.

The Pas calls itself the “Gateway to the North,” as though that was something people were actively seeking. The word Gateway is a misnomer. The Pas, with its movie theatre that showed only one movie at a time, its grocery stores that didn’t sell ripe vegetables, and community centres devoted to the holy religion of hockey, closed off more opportunities than it opened. Of course, The Pas had plenty of other stuff; it was abundant in opportunities to wear toques, balaclavas, and long underwear.

When we first got to Manitoba, we stayed with my aunts and their kids. They provided us with a single bedroom where we slept together in the same bed, all of us arranged around our mom to get maximum contact with her body. When Mom managed to find a house to rent, our aunts helped us move in their big pickup trucks. Moving day was quick because we had so many helping hands and because we had so little.

Our new home was located in Young’s Point, a small community about ten minutes outside of The Pas. Young’s Point had a square shape, with a skinny dirt road encircling it like a running track. In the centre, facing outwards, were tiny homes with one or two bedrooms. Some had running water; some did not. The sign that led into the housing complex read, “Young’s Point, God Lives Here.” Despite all evidence to the contrary, we took this as a good sign-sign.

All of our cousins declared that our two-bedroom bungalow was “cool,” though most adults would generally agree that it was dump. One of our older cousins, Norman, showed us how our kitchen window would serve us. “You could see a tornado coming through this window and then you could run out the back door!” He demonstrated by screaming and running out the door.

Norman was one of our favourite cousins because he liked to wrestle and he made us laugh all the time. He lived with my aunt and uncle as a foster child. He was with them for so long that he felt like a full cousin.

“Norman is so silly. Everyone knows the only place you can hide from a tornado is in the basement!” I told Celeste.

Celeste looked thoughtful. “Where is the basement?”

We went through the house opening and closing doors. Finally we went to our expert on everything housing and non-housing related. “Tabitha, where’s the basement?”

“There isn’t any.”

“Where do we go when there’s a tornado, then?”

It was Tabitha’s turn to look thoughtful. “I could always tie you to a tree.”

I suspected she was kidding. She didn’t smile so it was possible she was telling the truth. I would have tattled on her but a part of me wanted to be tied to a tree. Then I could see the tornado and be safe. Celeste agreed.

Our fear of tornados was not unfounded. Even though we were living in northern Manitoba and there hadn’t been a tornado in about a hundred years, we were originally from Saskatchewan where they were a regular occurrence. Mom brought her fear of tornadoes everywhere she went. “Look at the cloud, look how it’s turning black and making a funnel. That’s how they start. Next thing you know, your house is flying through the air.”

Celeste’s eyes lit up. “Like The Wizard of Oz?”

“No! Like . . . like . . . a horrible, bloody car crash.” Mom wanted her kids to share her fears.

Every week a water truck drove onto Young’s Point and pulled up in front of the houses to fill the tanks sitting at the back. My siblings and I were small and watched the water truck from our kitchen window, our cereal-smeared faces lit with glee to see any vehicle larger than the two door beaters that dominated our neighbourhood.

Tabitha and I went to school every day on a big yellow bus that roared through the complex every morning. It dropped us off at the Opasquayak School located on the south end of town. As a Kindergarten student, I wasn’t allowed to play with the big kids at recess. We had our own place to play, a small fenced off yard with two half-full sand pits that reeked of urine and boredom, and one set of swings — if you were lucky enough to get one of the swings, you stayed on it until recess was over, no matter that your legs went dead. On the other side of the chain link fence was the big kids’ area. They had multiple swing sets, slides, a merry-go- round and ball diamonds. Older kids ran through the area screaming with an exuberance not seen since ancient Greece banned bacchanalia. I yearned to be on the other side of the fence. But I was mindful of the rules and even when my older sister commanded me to crawl through a hole in the fence separating the big kids from the little kids, I shook my head and yelled, “I can’t. I’ll get in trouble!”

She called back, “Quit being a brownnoser and just come!” I stared at the hole and willed my body to move. It was no use; I sincerely believed the sky would fall on me if I broke the school’s rules. So instead, I stood there on my side of the chain link fence staring at my sister while she and her friends watched me from the other side, with a “What the hell is she doi

ng?” look on their faces until the bell rang. The worst part was seeing the disappointment written into the chubby cheeks of my sister’s face — I hated letting her down.

Kindergarten was a confusing time. I spent most of my day trying to figure out ways to please the teacher but always ended up annoying her. She asked us to rotate our way through the toys, rather than hogging one to ourselves. I did what she asked with enthusiasm, even going to the point of prying toys out of other kids’ hands when I felt they had played with them long enough.

The teacher laughed when another girl’s lisp made her say “shit” instead of “sit.” She didn’t think it was funny at all when I said, “hell” instead of “hello.” As a result of my failures to impress my teacher, I spent many afternoons sitting in “The Corner,” which had its own cubicle walls so that you could enjoy your punishment in privacy.

At the end of every Kindergarten day, I rode the bus home with my sister. The seats were huge and my feet would dangle freely. I enjoyed looking at the reflection of myself in the driver’s oversized mirror. Here I was sitting and kicking my legs and there I was, much smaller and off to an angle doing the same thing. “Stop kicking,” Tabitha said.

The small girl in the mirror stopped kicking and looked sad.

To distract me, Tabitha asked me about my day.

“Today Teacher . . . ,” I began.

“Did you forget your teacher’s name again?’

“Yes. Today Teacher gave us all cookies and Casey’s cookie got broken in half and she started crying.”

“Over a cookie?” Tabitha rolled her eyes.

“Casey cries a lot. So Teacher says, ‘look Casey it’s like you have two cookies now.’ And Casey stopped crying. So then I took my cookie and broke it into lots of pieces. And I said, ‘Teacher, I have lots of cookies too.’”

“And what did she say?”

“Stop making a mess.”

“Did you tie your shoes yourself today?”

I nodded my head. And the little girl in the mirror nodded her head too. Both of us were lying. Learning to tie shoes was turning out to be a nightmare. I had discovered it was easier to loosen the knot and slip off my shoes. Then at the end of the school day, I’d slip them back on and tighten up the knot again.

To distract her from my lie, I asked the question that was always guaranteed to generate an answer. “Where is Dad?”

“I already told you. He’s in Saskatchewan at our other house.”

“When is he coming here?”

“I don’t know. Stop asking everyone, especially Mom. Okay?”

“Okay.” I made my mouth big when I said it so that the girl in the mirror agreed with me.

You could see everyone else on the bus in the mirror. I made a face at myself. Then I saw an older boy staring at me through it. Caught, I quickly looked out the window. When I dared to look again, the older boy was making faces at me.

I tapped Tabitha on the shoulder. “There’s someone staring at me.”

“Where?”

“In the mirror.”

Tabitha looked in the mirror. Little kids picked their noses. Some boys bullied another boy. Girls sat backwards and flipped their hair as they talked to their friends. The older boy in the mirror was gone.

“What did he look like?”

“Big. Like he’s too old for this bus.”

“Well, I don’t see him.”

He had ruined the mirror game for me. Now all I had left was the window. I could barely see the little girl there.

I tapped my sister on the shoulder again.

“I need to go to the bathroom.”

“Why didn’t you go in school?”

“Teacher wouldn’t let me.”

Bathroom breaks were orderly ventures in Kindergarten. Like a short, co-dependent football team, we did everything together. When it was time to empty our bladders, we stood in straight lines and marched down the hallway.

That afternoon our teacher had read us a book about a little boy who was adventurous. “Little boys are always so naughty. I wish I had a little boy!” she had commented to our class, thus kicking off every little girl’s journey to self-hate in the room.

Inspired by the naughty boy, I climbed onto the sink and looked over the side of the cubicle. Casey was in there, doing her thing.

“Surprise!” I called down.

Casey looked up, screamed and — predictably — began to cry. She pulled up her panties and stalked out of the bathroom. Before I even had time to climb off the sink, the teacher was there waving her finger at me. I found myself back in “the corner” before I remembered that I still hadn’t used the toilet.

Tabitha rolled her eyes at my stupidity. “It’s only two minutes to our house. You can last two minutes, can’t you?”

I shook my head. I knew without looking at the little girl in the mirror that panic had spread across my face.

“Too bad cuz you have to wait.”

Tabitha was my guide to the world and as such was infallible. This time, however, she was dead wrong. I did not have to wait. The bus hit a bump in the grid road and the decision was made for me. My bladder released its heavy load. I felt sweet relief and my first thought was, “That’s not so bad. Actually it’s sort of warm and pleasant.”

The good feeling was quickly swept aside as my sister’s proclamations of “Gross!” informed the rest of the bus’s occupants to my accident. Soon, the kids were echoing my sister’s comment and adding new ones: “What a baby,” “that kindergarten baby peed herself,” and “I wish I hadn’t waited until now to eat my peanut butter sandwich.”

Fortunately it happened right outside our house. The bus door opened and Tabitha ran inside and announced my shame to everyone. I followed at a much soggier pace. Mom led me into the bathroom and sat me on the slop pail. The slop pail — if you need any further explanation — was a metal pail about three feet high that served the same function as a toilet, except of course, it did not flush.

“What’s the point of that?” Tabitha asked. “She already peed all over me!”

As it turned out, there was more detritus that needed voiding. My bowels relaxed as their burden was unloaded.

“See? There was a point,” Mom laughed and David and Celeste joined in. Even I laughed.

“This is the grossest house ever!” Tabitha stalked away.

The slop pail was uncomfortable but Mom claimed we were lucky to have it. “Hell of a lot better than when I was kid. Back then you had to freeze your bum off outside.”

“You peed outside? Like a dog?” I asked.

“No! In the outhouse. We weren’t animals, for God’s sake.”

“What’s an outhouse?”

“A little building that’s outside the house where you go to the bathroom. You kids don’t know anything about roughing it, that’s for sure.”

The slop pail was the next step up on the bathroom evolutionary ladder. While never a pleasure to use, it was even more difficult to operate if you were short. My hands would have to go down first, on either side of the slop pail, and then I’d have to jump a little and get my butt on. But very carefully because when it comes to slop pails, failure is not an option. If you slip, you might fall in the murky waste — bum first — or, much worse, tip it over and decorate the bathroom with the contents. That’s a mistake you only make once in your life. (Or if you are my brother David, every single day for a month until Mom decided to move him back into diapers.)

Despite the slop pail challenges, our cousins loved coming to visit us. Young’s Point was off the reserve; it was undiscovered territory and they were eager to make their mark. The highlight of every visit was walking through the woods to a convenience store so small it was basically amounted to an enterprising hippie couple who sold chocolate bars and potato chips out of their kitchen.

“We could get mugged,” Norman said, peering into the trees. “Up in the city, people get mugged all the time.” Then he etched his name into a fir tree with his kni

fe.

I stared into the dark woods trying to discern the muggers. On a walk with Tabitha, she dismissed my concerns. “As if. There aren’t any muggers here, just bears,” she said as she practiced smoking with a twig.

Tabitha not only knew everything, she was willing to try anything. Her long legs discovered a stream running through the woods and she immediately began to wade into it. “What about polio?” I asked her, even as I scratched the huge polio vaccine scar on my arm.

“There’s no such thing,” she said. “Now get in here and wet your feet.”

I moved slowly, entering only one foot at a time, sucking in my breath as the cold water found its way through my runner, through my sock to my foot. “I got a booter! I got a booter!” I cried.

Tabitha shook her head. “I told you to take your shoes off!” she said, as she ushered me and my wet feet home, sloshing all the way down the muddy path.

Walks with Tabitha were important for figuring out the world.

“You know Tabitha, I can’t tie my shoes. Other kids can do it, but I can’t,” I said, on another trip to the junk food store.

“Did you try the Bunny ears?”

“Yes, I tried the Bunny years.”

“E-ears.”

“I thought you said, Y-Years.”

She kneeled down. “You make two loops, each one looks like a Bunny ear. You see?” she explained.

I sighed in relief. “Oh right. I thought I was going crazy.”

“You’re not crazy.”

“I have another question. How come I can’t ride my bike yet?”

“Cuz your legs are too short,” she said.

“So when they grow, I can do it?”

Tabitha lingered on her answer for a few seconds. I waited — my heart clenched. Oh please don’t say I won’t ever ride my bike, I have to ride my bike! Please don’t say there’s something wrong with me that can’t ever be fixed.

“When your legs grow, you’ll do it.”

“Thank goodness.” I let out my breath. “I have another question. How come the priests take our money?”

Nobody Cries at Bingo

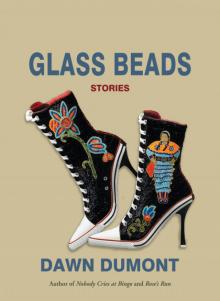

Nobody Cries at Bingo Glass Beads

Glass Beads